REVIEW: ‘Manet: Three Paintings’ at The Frick

Photo: Édouard Manet, Fish and Shrimp, 1864, oil on canvas, Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena, California / Provided with permission.

NEW YORK — Saying nothing against art retrospectives that can amass collections of more than 100 or 200 items, there is something appreciative and expectantly contemplative about a mini-exhibition with only a handful of pieces on display. Case in point: Manet: Three Paintings From the Norton Simon Museum, on view at The Frick Collection in New York City through Sunday, Jan. 5.

As the title suggests, the Frick has been temporarily loaned three Édouard Manet works — nay, masterpieces — from the well-respected Norton Simon, an institution in Pasadena, California. The exhibition continues the reciprocal loan agreement between both museums, according to press notes.

The three works by Manet are wonderful selections that offer viewers a chance to see the painter’s diversity of subject, his unmistakable style and handling of light, perspective and angle. Well-situated in the Frick’s so-called Oval Room, Manet: Three Paintings invites deeper introspection, and a nearby couch seems to almost cement that invitation with a postage stamp.

On a recent visit, this reviewer sat down and took in all three compositions. There is “Fish and Shrimp” to the right, a clever 1864 still life featuring two fish — one large and glistening, the other skinny and shiny — entangled in an embrace that could be viewed as loving, except, of course, they’re dead, ready for the viewer’s culinary enjoyment. To the left is a small pile of shrimp with the tails and heads still on. As helpful exhibition notes point out, a white tray frames the fish, offering further perspective and depth to the pesce on view.

To the left in the Oval Room is “Madame Manet” from 1876. The oil on canvas is similar in size to the “Fish and Shrimp” painting, but this portrait has a different resonance. Sitting on the central couch, contemplating Manet’s brush strokes and compositional choices proves to be an educational experience. One notices that there’s a finite detail near his wife’s face and carefully done hair, with a light, breezy reddish brown found amongst the locks. Look close, and one can find the green teeth of a hair piece — perhaps a comb — sticking out from above the woman’s right ear.

This detail grows more obscure and general in nature as viewers’ eyes descend to Madame’s face and especially her white shirt, necklace and black coat. Manet’s strokes become wider and more forceful, not in a sloppy way, but in a clever way of drawing the eye upward and not downward. Its rough, unfinished feel deemphasizes the outfit and lets the shimmering quality of his subject’s face become that much more radiant.

(Exhibition notes also point to a hat that once donned his wife’s head. It’s now gone, but the darkness from the rough draft still encircles the subject like a ghostly image.)

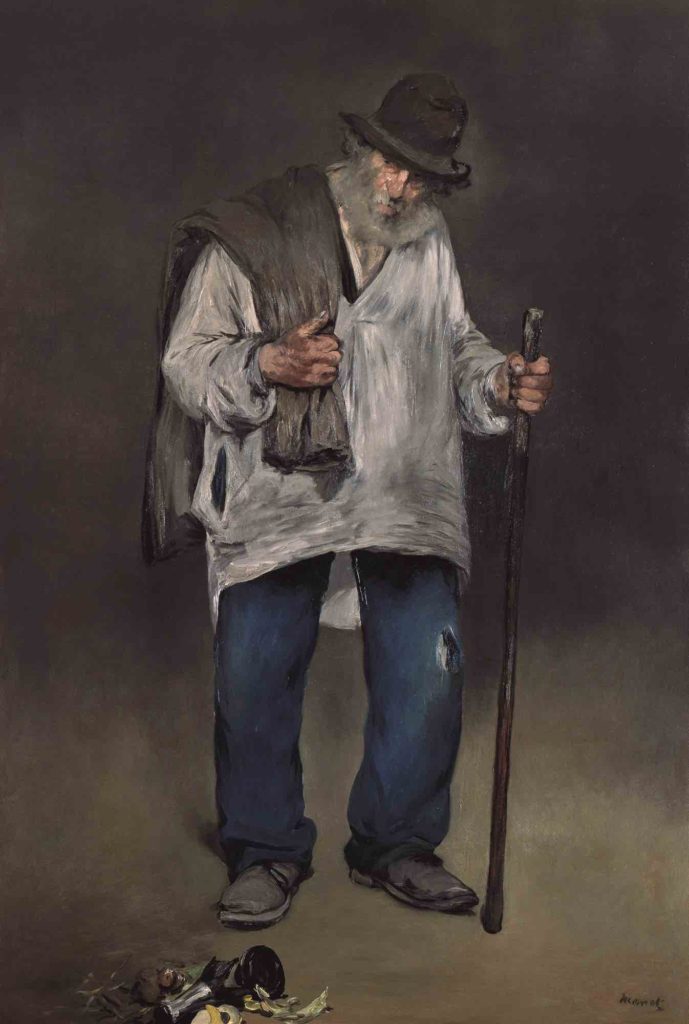

The pièce de résistance is the central painting, the largest of the three: “The Ragpicker” from circa 1865-1871, with a possible reworking by Manet a few years later. This is a monumental feat of artistry, surely the highlight of this trio show. The subject of the work, with a slight hunch in his shoulders and a look downward and right, is a romanticized ragpicker, walking with a cane in his left hand and a coat slung over his right shoulder. It’s a full-body rendering against a darkish background with a destroyed still life of flowers in the foreground, its pieces spilling off the canvas.

The effectiveness of this almost life-size painting can be found in its subtlety: the eyes peeking out from beneath the brim of the ragpicker’s hat, the clenched right fist around the coat, the equally clenched fingers around the cane, the look into the distance, the promise of something to come.

The beneficiaries of this reciprocal agreement between The Frick and Norton Simon Museum are those viewers who can catch three intricately painted works from a bonafide master of 19th-century France. Its brevity is its greatest strength because the centrality of the three compositions allows attendees to pause, to gaze, to learn — perhaps in the manner Manet had originally intended.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Manet: Three Paintings From the Norton Simon Museum, organized by David Pullins, continues at The Frick Collection in New York City through Sunday, Jan. 5. Click here for more information and tickets.