INTERVIEW: ‘Saints of Failure’ explores LGBTQ identity and issues of faith

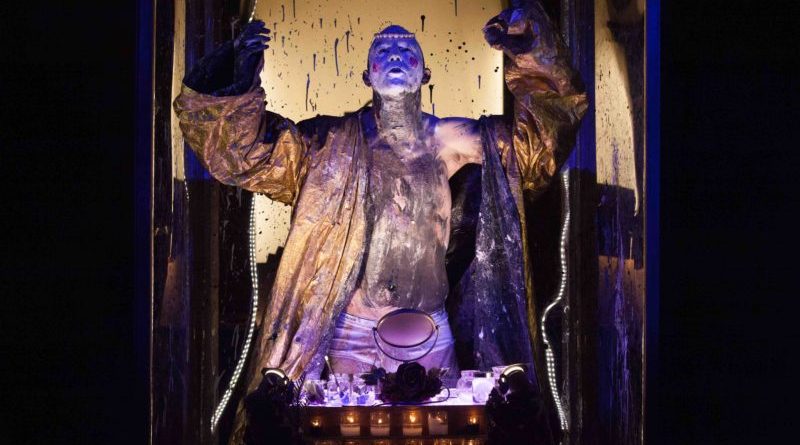

Photo: Ryan Connaro wrote and stars in Saints of Failure. Photo courtesy of Carolyn Brown / Provided by Press Play with permission.

The new play Saints of Failure, written by and starring performance artist Ryan Conarro, explores his experiences growing up gay in the Roman Catholic Church. Throughout the evening, which continues through Nov. 9 at New York City’s Lafayette Ave Presbyterian Church, Conarro dives deep into his identity and his past, all the while applying paint to his face at the direction of coach and designer Risha Rox.

The creative evening of theater, directed by Ellie Heyman, looks to investigate LGBTQ identity and how it impacts and influences the American Christian experience, and vice versa.

Conarro, who spent time living in Nome, Alaska, is the creative force behind ALAXSKA/ALASKA and this hour forward. When creating theater, he wears many hats, including interdisciplinary artist, audio storyteller and community engagement facilitator. He is currently artistic director of Generator Theater Company and artistic collaborator in residence at Ping Chong + Company.

Recently Hollywood Soapbox exchanged emails with Conarro about Saints of Failure. Questions and answers have been slightly edited for style.

When did the first ideas for Saints of Failure come to you? Was there a particular creative spark that kickstarted the project?

It was 2014, and I was starting my final year of graduate school in Goddard College’s Interdisciplinary Arts Program. I’d made a solo piece earlier in my school journey — this hour forward, a piece exploring gay marriage equality and using live interaction with video projections — and that piece had enjoyed a successful run and tour.

For my final MFA project at Goddard, I had the big idea that I’d make another solo piece that would build on the successes of this hour forward. But I didn’t like what I was making. All my efforts felt inauthentic and grasping; I was trying really hard to make something good and sort of approve-able. And I was complaining about it all along.

Finally my adviser, Laiwan, said to me, ‘Why don’t you just quit this project and start something new? What is this thing with you where you refuse to quit anything?’ I was taken aback. This became a real lesson for me about being an artist — that it’s essential to take real risks, if we’re going to make work that really goes into unexpected and authentic territory.

The first thing that sprung to mind when Laiwan asked me that question was the sudden, accidental death of my close friend Julia when I was 17 years old. My response to her death was to try to bear down and fight through the grief, rather than allowing it to affect me. And I realized that that was a pattern I’d habituated, and it wasn’t good for me as an artist or really as a human.

So a new project began: what if I try to allow for, and even embrace, my own moments of failure? It’s really hard to do that because the desire to get it right creeps in all the time. The story of Julia’s death, and my response to it, is now one of the personal stories I tell in Saints of Failure.

What was your experience like growing up gay in the Catholic Church?

I was a good kid, and I was eager to please. I also loved, and still love, the sumptuous rituals and traditions and imagery of Catholic spaces and Masses. The Church, my family and the culture we moved through all were really approving of my staying within the boundaries of the Church’s norms. I was an altar boy; I sang in choirs; I was in the Catholic Newman Club in college. I know many other LGBTQ Catholics have had similar experiences.

For me, I internalized the Church’s messages very thoroughly, so it was a real rupture for me, internally, to finally allow myself to acknowledge that I’m gay. When I came out at age 21, it was just as much to myself as it was to my family and friends. It all happened at once for me. There’s really no way that living a ‘gay lifestyle’ — which is to say, having gay relationships or sex or intimacy — can be an OK way to live, in the Church’s eyes.

The Church actually says that it’s OK to be gay, that it’s not my fault, but that it’s a sin to act on it. That’s a line of text from the performance: ‘You may BE this, but you must not DO this.’ What a tragic thing, to be called upon to resist and avoid and run from intimacy and physical love — such essential aspects of being a human being.

What is your faith like today?

Like others, I consider myself more spiritual than religious these days, and I think my faith in some higher force, and some universal connection, is both strong and confused, all at once. I still seek out religious spaces as places to reflect on what this whole life thing is all about — and as places to do that with other people, in community with each other.

So now I go to Lafayette Ave Prebsyterian Church, where Saints of Failure is running. It’s a beautiful space; it’s open and welcoming in ways that are almost startling sometimes, for me. But I still question all of it, fundamentally; I’m not sure I’m not secretly an atheist under all my bluster about faith and sexuality and getting to church by 11 on Sundays. Maybe I’m just agnostic. I really enjoy sitting with the questions, I guess. I think for me that sitting with questions is itself such an important aspect of being a human being.

How is makeup utilized in Saints of Failure, and why did you think this was an important addition to the show?

Risha Rox’s makeup design is an essential aspect of the show. It illuminates themes and imagery; it evokes other-worldliness or saintliness; and it’s a narrative tool itself. Sometimes the makeup tells the story without having to use words at all.

Risha and I met in the Goddard Interdisciplinary Arts program, and this project was a collaboration from the beginning. In the spirit of failure and risk-taking, I wanted to dare to make something where I could try to really physically embody grotesqueness, pain, all the yucky stuff — and playful outrageous fabulous stuff, too.

Risha was excited about imagining these new saint icons with me, and she was into the challenge of crafting makeup looks that I could apply live as a performer onstage. So we spent much of the next four years flinging paint around apartments and rehearsal spaces, blowing baby powder everywhere, and cracking eggs on my head. You know, like the very serious performance artists that we are.

How physically and emotionally draining is each performance?

I actually find the experience of performing the show to be energizing. Ellie Heyman, my excellent director, talks about this piece as a pressure cooker — like the energy wants to stay tight and contained and grow and grow and grow. I feel that, and it leaves me at the end of the show really ready for a meal and a drink and some juicy conversation with people.

At the same time, the show ends in the most vulnerable place I’ve ever experienced as a performer. So I also feel a little sheepish about going to the lobby post-show, to find friends and family there. Sometimes we don’t know quite what to say to each other. I think, I hope, that the vulnerability in the show is an offering to people, to spend a little time together in a place that we don’t often go with each other.

How has your experience in Alaska informed your work? Are you forever changed because of that time in your life?

Absolutely changed. And it’s ongoing — as is my work and life there. I still get to spend chunks of each year there, I’m so glad to say, and I’m still making work there as well. Living in Nome and then Juneau has given me supportive places to try new stuff as an artist and also to figure out how to do that within small communities where I want to responsibly open dialogue with people who are friends and neighbors of mine. These are arts-friendly places and open and welcoming places; in my experience, people can really find and be themselves there. Of course, aren’t we all always doing that, finding ourselves and trying to be more fully that? I hope we are.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Saints of Failure, written by and starring Ryan Connaro, plays through Nov. 9 at the Lafayette Ave Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn. Click here for more information and tickets.