INTERVIEW: ‘Lady Romeo’ details revolutionary life of Charlotte Cushman

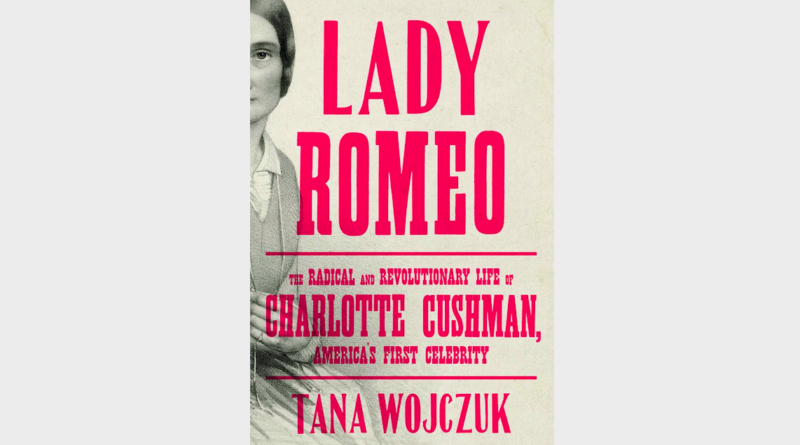

Image courtesy of Simon & Schuster / Provided by official site with permission.

Although Charlotte Cushman may no longer be a household name, the Shakespearean actor enraptured theatrical audiences in the 19th century. The Boston native, who went on to find success in London and throughout the United States, was known for several prominent roles from the Bard’s oeuvre, including Lady Macbeth and Romeo.

Her life is the subject of a new biography by Tana Wojczuk. Lady Romeo: The Radical and Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America’s First Celebrity is now available from Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster.

In the book, Wojczuk details Cushman’s humble beginnings in Boston and her early need to provide for her mother and siblings. The only professional avenue that she saw available was acting on the stage, which at the time was reviled by the upper-class, who thought the art form was one step above prostitution. This dichotomy is an interesting one: often, the public would enjoy dramas and comedies beneath the proscenium, but parents would turn woeful if their children became traveling performers.

Cushman had no other choice, so she tried out for a production and almost instantly won favor. Eventually her budding celebrity status took her to New Orleans, New York City and London, where she upended expectations and even taught a thing or two to the British actors who had a virtual monopoly on performing Shakespeare.

Most memorably, Cushman lived a mostly open life as a queer woman, having partners and eventually someone she considered her wife. She donned the stage in female roles and male roles, winning acclaim for her turn as Romeo against her own sister performing the Juliet part. She even moved abroad at one point, setting up a small community of artists in Rome, welcoming free expression into her household.

As she grew older and more infirm, relegated to performing from a chair on New York City stages, the audiences still packed the house. Her final performances were paramount events, attended by the toast of society, including the critics who had either loved her or berated her over the years (Walt Whitman was an early convert). When she died, it was as if a titan had passed from this world.

For Wojczuk, the entry point to Cushman’s story was her own adoration of Shakespeare’s works.

“So I was always really interested in Shakespeare,” the author said in a recent phone interview. “My parents started taking me to Shakespeare when I was a little kid, and it always seemed just really exciting and accessible to me. Many of these festivals are free or really cheap, and so it’s sort of a fun, free entertainment. And so later, when I started reading about Cushman, it really seemed like she helped create that really exciting culture in America that views Shakespeare as something we can adapt into movies and change and rewrite as we like, but I was also really excited by her queer code-switching. She was a queer woman who lived with female partners, but because she played men’s roles on stage, like Romeo and Hamlet, she was sort of seen more as a man. And so her masculinity off-stage was more acceptable.”

The early part of Wojczuk’s book looks at the lingering influence of the Puritans in the United States and how they essentially attacked live theater and labeled Shakespeare as sinful, and this meant actors were essentially evil incarnate.

“But the Puritans I think were sort of also in competition with the theater, as I say in the book, for butts in seats,” she said. “And the culture that Cushman grew up in was very puritanical, and so she would never have been allowed to go on stage if disaster hadn’t happened in her childhood where her father abandoned the family. And they had no money and no male child old enough to work, so she had to find a way to make a living for her family.”

After reading Cushman’s life story, one realizes she was an early feminist, a term that Wojczuk definitely thinks applies to the performer’s life. Behind the scenes Cushman worked to support women in many different ways, including giving out loans to female artists and gathering a group of female friends in Rome for a proto-bohemian artist colony.

“Even though she was seen as very masculine and played men’s roles, she also was able to have a very unusual amount of freedom for a woman because of her success and her wealth toward the end of her career,” Wojczuk said. “So she was seen as an icon by women — like a young Louisa May Alcott, who saw her and had a stage-struck fit and then wanted to follow Cushman into acting, but her family talked her out of it.”

There are numerous sources of information that Wojczuk pulled from to bring Cushman back to life. One pivotal book was Cushman’s autobiography, which was dictated to her wife, Emma Stebbins (they were married in all but law). That dictation was cut off when Cushman died at the age of 59, but Stebbins filled in the blanks and used the actor’s letters to complete the text.

“A huge amount of letters are in archives all over the country, and some are even in the Library of Scotland,” the author said. “And so it was really important to piece together a lot of unpublished material to see how she really lived and what she really thought, and there’s a lot of material about queerness that never shows up in the public documents, like newspaper articles, for example. But people are writing about it in private letters, so, for example, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, when she met Cushman and her then-partner Matilda Hays, said ‘Oh, they dress alike. They go everywhere. They must be married.’ And when she wrote this to her sister, her sister responded, ‘Yeah, it’s pretty common. It’s not unusual.’ So these things were recognized even if they weren’t publicly named.”

She added: “And her memoir was ultimately published. It wasn’t all her writing. It was a combination of her talking to her partner and then her partner filling in some of the blanks.”

As Wojczuk delved deeper into Cushman’s life, she became even more fascinated by early American theater and entertainment culture. Cushman was born in 1816, a time that the author said the United States was considered a “cultural backwater” and a “nation of campers.” The relatively young country couldn’t compete artistically with the likes of England and France, but this was also the time that America started to find its voice through writers like Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In fact, Emerson was Cushman’s pastor in Boston.

“Cushman is an answer to a question a lot of these young Americans were asking, which is where is American genius, what is it going to look like,” she said. “Except for opera, [theater] was a fairly low brow venue. … But they recognized her as a genius. Whitman was one of the first to write about her as a genius before she ever became the celebrity that she ultimately did become. … Her Lady Macbeth was the role that she used to bookend her life. It was the first acting role that was offered to her, which was really surprising because it was a major role, and it was the role that she did in her final performance. And Romeo is the role that made her famous when she first went to London and played it opposite her sister as Juliet, and she reinstated the full text of Romeo and Juliet in London because it had been performed in a version where Romeo and Juliet wake up at the end. … I will say that there’s notes and letters at the end of her life that she did get a little tired of playing the same roles, but that was what everyone wanted her to play.”

Her Romeo proved famous, in Wojczuk’s mind, because this title character was Italian, passionate and young, which ran counter to the tight-laced American and British cultures in the 19th century.

“I also think that Cushman was able to play with different versions of masculinity with that character,” she said. “With one of Romeo’s battles, a duel with Tybalt, she knocks the sword, and it flies toward the audience and scares everybody. Then at the end when she sees Juliet, played by her sister who is dead, she cradles her and weeps over her. This expression of emotion was very moving to men and women, and a lot of audiences really like to see a man able to express these deep, passionate feelings. But then other critics found it too feminized, in fact, so I think there were really complicated pictures on the stage of a woman as a man acting in all these different, interesting ways that people found really exciting and different. I also think she loved to read and reread Shakespeare, and I think she understood the language and the text and was able to make choices that really clicked with the text. It helped make Shakespeare alive and not just melodramatic, like acting her points, which is what people were used to seeing.”

Cushman, despite being a revolutionary and an early feminist, was also someone who was placed in the history books because of what male critics thought of her performances. Critics at the time (a tradition that continues to this day) had a tremendous amount of power, deciding what was culturally significant and what was not. These reviews provided interesting details for Wojczuk.

“Even the day she died, there’s a columnist who felt free to say even though Cushman was a great actress, thankfully no woman will have to debase herself by playing men on stage,” the author said. “And during Cushman’s life, definitely men had a lot of control over her career, including critics but also theater managers, but there was also an uptick of women writing columns at the time. So there was an explosion of the popular press. To a great extent, her success a lot of it came from support she got from female writers and critics in a lot of these new magazines that were popping up at the same time. Even though the most powerful were still men, I think there was room to write about how beautiful they thought she was, like her masculine face and features they found really attractive, for example. And they found her a very convincing and seductive man.”

Wojczuk added: “She paved the way for playing men’s roles in a really serious way. … There were a lot of women actresses coming up even during Cushman’s own life who were deeply influenced by her and who she kind of fostered and who were influenced by her more thoughtful and intellectual acting style.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Lady Romeo by Tana Wojczuk is now available from Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster. Click here for more information.