INTERVIEW: Enduring lessons of the Salem witch trials are focus of PEM exhibition

Image: Tompkins Harrison Matteson’s “Trial of George Jacobs, Sr. for Witchcraft,” 1855. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey R. Dykes. Provided with permission.

The witch trials that occurred in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692 were a horrifying display of false accusations, puritanical religious fervor, public executions and legal wrangling that greatly impacted people in the local community. The historical episode resulted in the deaths of 25 innocents, according to the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, which is finishing up a celebrated run of an exhibition that highlights the history of the horrors.

The exhibition utilizes documents, objects and paintings from PEM’s vast archive, and they are displayed at the Essex Street institution for those lucky enough to visit in person. But for others who are unable to travel due to COVID-19, PEM has also made the artifacts available online with a unique, 3-D view that allows patrons to virtually walk through the space and experience the story from the safety of their home.

“Interestingly, the last Salem witch trials exhibition that was put on by the Peabody Essex Museum was in 1992, so it’s been nearly 30 years since we’ve had anything like this on view, even though we have this phenomenal collection,” said Dan Lipcan, co-curator of the exhibition and head librarian at PEM’s Phillips Library. “What happened was that our former director, Brian Kennedy, approached Dean Lahikainen, who is the other co-curator of the exhibition. Dean’s in charge of American Decorative Art, and [Brian] essentially said to him, ‘We’re going to do this exhibition, and I want it to open this fall.’ This is back in, I think, February a year ago, and Dean very graciously said, ‘Well, don’t you want to have the library involved, and shouldn’t I bring Dan into this?’ And that’s kind of where it began, so we had an extremely short period of time to pull this together.”

Then, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the museum and other cultural institutions. This made their job of planning for the exhibition exceedingly more difficult, but they somehow found a way to organize the artifacts, ensure the accompanying labels were historically accurate and launch the exhibition in September 2020. It will run through April 4.

“It was a challenge to put it all together,” Lipcan said. “I think one of the reasons we’re doing this now is #1 we’re interested in reengaging with our local communities, and #2 some of the injustices that we’ve seen happen, or that have continued to happen, and have come to more people’s consciousness in the last few years, really drove home the idea to us that we have something to learn from the witch trials that we can apply to our current situation, to our current society.”

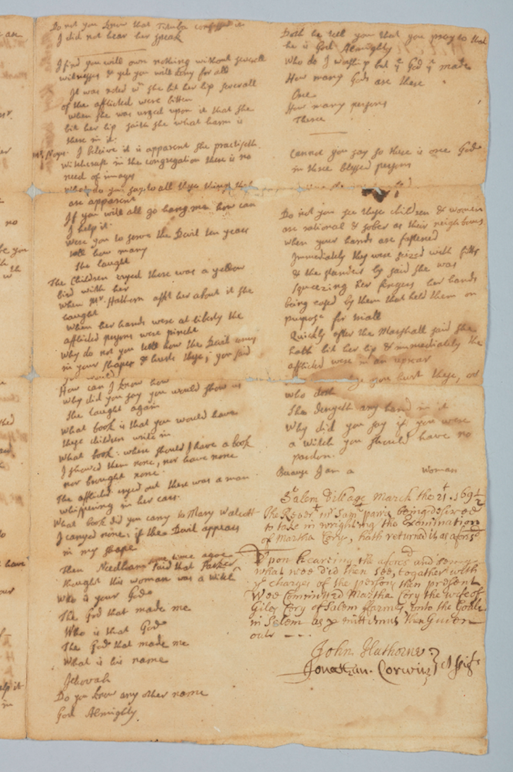

Samuel Parris and John Hathorne. Examination of Martha Cory, March 21, 1692. Ink on paper. ©2020 Peabody Essex Museum, Photograph by Kathy Tarantola. Provided with permission.

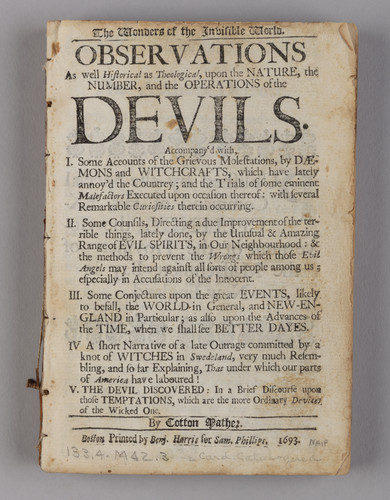

Cotton Mather’s “The Wonders of the Invisible World,” 1693. © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. Provided with permission.

There are many interesting and informative pieces within the show. There’s the death warrant for the execution of Bridget Bishop, for example, plus invoices for the local jail keeper, testimony from accusers and the physical examinations of the accused, according to a PEM press release. There’s a trunk once owned by Judge Jonathan Corwin and a sundial believed to have been John Proctor’s.

“The objects are drawn from PEM’s object collection, if you want to call it that, and the documents are from the Phillips Library,” the co-curator said. “Most of the documents on display are owned by the state, by Massachusetts in the Supreme Judicial Court Archives, but they are currently housed and stewarded in the library under care of me and my staff. But everything is essentially from PEM and its collections, which is a great opportunity for us and a good opportunity for us to show the riches that we possess.”

Lipcan said he believes many of these delicate papers survived because they were official court documents. There was the definite shame of succeeding generations of Salem residents and court officials, which might have led to the destroying of the evidence, but there was an abiding interest in maintaining the records and detailing the activities of the court. That said, these examinations and invoices and testimonies are extremely fragile and sensitive to light. That’s one of the reasons this temporary exhibition cannot become a permanent fixture at PEM.

“We are very fortunate that so many of these documents have survived,” Lipcan said. “We have about 550 in our possession, so it really is a remarkably well-documented series of events in crisis. … There was a lot of shame associated with the trials and what people did and how they acted, or how they didn’t act, as you saw in the exhibition. I think we’re still dealing with it as a community. The last person that was accused that still had not been exonerated was finally cleared in 2001, and I think there still remains one or two people out there whose records have not been cleared, although there’s a little bit of confusion about whether or not they were actually cases of witchcraft. But this is still happening. The memorial was just built in Salem in 1992, and the memorial at Proctor’s Ledge where the hangings happened, that location was recently discovered. And then a memorial was built and dedicated just a few years ago. It is still very fresh, which is really interesting.”

Judge Jonathan Corwin House (The Witch House) in Salem, Massachusetts. © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. Provided with permission.

Proctor’s Ledge Memorial in Salem, Massachusetts. © 2020 Peabody Essex Museum. Photography by Kathy Tarantola. Provided with permission.

To help the curators on the text needed to bring this time period to life, they relied on the scholarship of Emerson W. Baker, professor of history at Salem State University and author of A Storm of Witchcraft, and Richard B. Trask, town archivist at the Danvers Archival Center at the Peabody Institute Library in Danvers, Massachusetts.

“We have a large body of scholarship on the witch trials,” Lipcan said. “Publications continue to come out all the time based on additional research into the documents and into the lives of the people who were involved. We were really fortunate to have the expertise of Emerson Baker. … He wrote a book called A Storm of Witchcraft, which is really, in my opinion, one of the best books that I’ve read on the trials — really takes in the whole crisis, distills it down, explains the personal relationships of people and links it to what’s happening in Salem today in its aftermath, so he was a consultant for us. He did the initial draft on some of the larger section panels because he has decades of experience and knowledge that he’s built up over the years in his research.”

Trask proved pivotal as well, and he’s considered the “grandfather of witch trials scholarship.” Both historians reviewed the selection list, read the accompanying text, checked for accuracy, and incorporated their opinions and feedback on what they saw.

When walking through the exhibition, either in person or virtually, one can appreciate the visual storytelling of the witch trials as well. Yes, there are many documents to read, but there are also select paintings depicting the historical events. One painting is “Trial of George Jacobs, Sr. for Witchcraft” by Tompkins Harrison Matteson. Depicted in the work of art is Jacobs’ granddaughter, who accuses him of witchcraft.

“I think at a very, very basic level, we recognize that filling a room with a set of documents is not the most visually compelling way to tell a story,” the co-curator conceded. “And the paintings really bring the trials to life, even though the costuming you see, the clothing you see is from a different time period almost entirely. They look like Dutch paintings, but they bring some color and some life and some bodies into the exhibition in a way that the documents really can’t. So at a basic level that’s what we were trying to do, enliven the display a little bit, and I think the fact that these two paintings were later interpretations is just further evidence that the trials remain compelling to people and have been compelling to people ever since they happened.”

Deciphering the texts in the exhibition was difficult for Lipcan, Lahikainen and their staffs. Although one can read the cursive words, picking up on names like Tituba and Proctor, some of the legal language is arcane and needs a historian at the ready. Lipcan called it a “real challenge,” especially when the examiners took liberties with their spelling.

“The penmanship can be really difficult to read,” he said. “There are a couple of documents that are written by Samuel Parris, which actually are quite clear. His handwriting is very small, but it is very clear. And it does take time to kind of learn to read that penmanship, and it does take a little bit of translation to understand what is going on in a given document. I’m still learning all this myself. One of the things that we considered very seriously was how we would present the documents to the visitor. We realized, of course, a month or two into the planning that there’s no way that we would be able to provide transcripts for people to read while they were there in the gallery because the whole issue of touching things was very serious, and I think we realized that we needed to keep the exhibition spacious and that we really couldn’t provide any sort of seating or handouts that people might be able to use, which was unfortunate. … We tried to communicate the important and salient points of the documents in the label text and in the character stories we provided.”

Ultimately, PEM is after an authentic retelling of these historic events. Lipcan stressed the need for truth and fact when describing the 1692 witch trials, and the authentic objects and documents help the museum tell that story.

“We pulled out quotes from various documents in order to tell the stories of people who were caught up in this crisis, and I think it was really important for us to tell the historical and factual story because you do get all sorts of different kinds of interpretations from various places,” Lipcan said. “So we wanted to counter some of those myths, but also say this is what really, really happened, and make it human and bring it to a scale that people today could identify with, so that folks visiting could recognize that Mary Eastey was a real person. And she was accused and tried and hanged. She had a family. She had thoughts and feelings just like you do and I do, so that for us was really, really important.”

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

The Salem Witch Trials 1692 exhibition continues through April 4 at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Click here for more information and tickets.

James Symonds, 1633-1714, Salem, Massachusetts. Valuables cabinet owned by Joseph and Bathsheba Pope, 1679. Oak, maple, iron and paint. Photo courtesy of Dennis Helmar / Provided with permission.

John Smibert’s “Portrait of Judge Samuel Sewall,” 1733. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. Photography by John Koza. Provided with permission.