REVIEW: MoMA’s ‘Transmissions’ finds connections between Latin America, eastern Europe

NEW YORK — Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980, which runs at the Museum of Modern Art through Sunday, Jan. 3, is a thorough, complex display of challenging, unconventional pieces that draw eternally interesting connections between these two important regions of the world. Anyone with even a basic understanding of the history of Latin America and eastern Europe during these tumultuous decades know that political unrest was the rule of the day, and issues of oppression, expression, culture and censorship were debated and discussed on a regular basis. By placing these two worlds together in one common exhibition, MoMA has found parallels across cultures that hint at a shared experience of redefining art and championing alternative viewpoints.

Taking up the sizable exhibition space on MoMA’s sixth floor, near a new show highlighting the work of Joaquín Torres-Garcia, Transmissions begins with Eduardo Costa’s “Names of Friends: Poem for the Deaf-Mute,” which can be seen on a large TV screen in the entrance hall. The video installation from the Argentinian artist was shot on 8mm and features a display of Costa’s mouth reading off the names of his friends. There is no sound, but one realizes that the message is still being broadcast. Tthe names are silent, only deciphered after focusing on the lips of the artist. It’s a fitting start to the exhibition.

Nearby, hanging above the formal entrance to the galleries, is Antonio Dias’ “The Invented Country (God-Will-Give-Days),” a simple red flag made of satin and brass. Dias, born in Brazil, has offered a revolutionary symbol of a flag mounted high above, but somehow its slight size and fragility offer two interpretations: hope beyond any measure of oppression (a flag of survival) or despair in that the art piece, because of its relative size, is almost lost on the viewer (a flag of defeat). MoMA’s gallery label states that the work is an “emblem of failed state-sponsored revolutions and of the smaller utopian experiments that replaced them.”

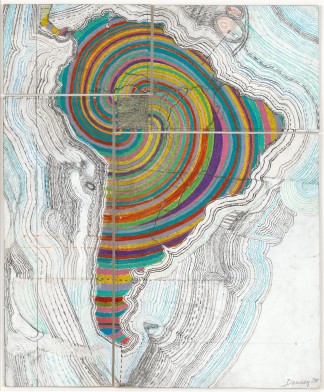

Juan Downey’s “Map of America” refashions the South American continent with a whirling array of colorful lines, breaking down barriers between countries and cultures and creating one diverse mass. David Lamelas’ “Time” is a performance piece where museum attendees stand in line on a piece of tape and relay time intervals to their partners next to them. The piece from the Argentinian artist is performed at MoMA on Fridays.

Even though the opening gallery space focuses on Latin American artists, the rest of the exhibition is a varied combination of both regions. There are many highlights from artists both known and obscure. Lygia Clark, a favorite sculptor of so many, has two pieces in the first gallery. “Poetic Shelter” features her characteristic sheet of metal pulled and cut in such a way that it gives three-dimensionality to the otherwise two-dimensional piece. Ditto for “The Inside Is the Outside,” which is shinier than “Poetic Shelter” and thus more striking.

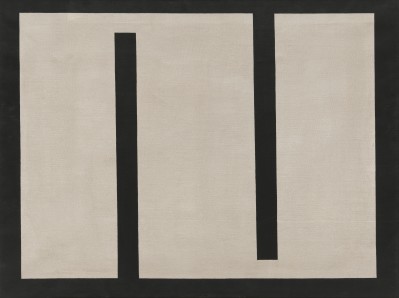

The recently deceased Ellsworth Kelly is represented by “Running White,” a stark oil on canvas that offers an interplay between black-and-white imagery. A white line is wrapped in an overflowing circle on the canvas, almost as if the painting is too big for the canvas, which is unable to hold Kelly’s full idea.

Julije Knifer is one of the real highlights of Transmissions. The Yugoslavian artist’s “Meander No. 5” has a visual similarity to Kelly’s piece, with both using black-and-white images to display a simple, yet perplexing series of lines and empty space. Unlike “Running White,” the “Meander” creation is more rectangular, as if the snake in Kelly’s canvas has straightened its back and has the ability to move in perfect 90-degree angles. Also, both pieces allow an interesting thought: What is the main line? Where should the focus lie? Has Knifer drawn a white serpent on a black background, or are these black walls on a white canvas?

Light is the focus in Julio Le Parc’s “Double Concurrence — Continuous Light, 2.” Viewers look through a small window at a series of hanging plastic squares that move like a wind chime at the slightest nearby movement. Watching the pieces move in and out of a red light, reflected off a mirror in the background, is almost like watching an alternative heartbeat. One’s stillness cannot keep the squares from moving, from twirling on their nylon threads in a perpetual dance of light and movement.

François Morellet, from France, might seem an unlikely addition to the show, but his “Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares Using the Odd and Even Numbers of a Telephone Directory” is one of the strongest pieces in Transmissions. According to the helpful wall notes, Morellet’s piece is essentially a random display of red and blue squares that are meticulously painted in horizontal and vertical lines. Apparently one color represents odd numbers, and the other represents even numbers. What viewers are seeing is an alternative display of the seemingly random numbers in a telephone book. The piece begs for a multi-minute viewing to see if patterns can be found in what is supposed to be a spontaneous and disorganized array.

Jesús Rafael Soto has a few pieces represented, with the most interesting being “Untitled,” a sculpture of wood, metal and nails. It looks as if Soto found the piece in an alleyway, as if it were a discarded hunk of construction material. However, something about the rawness of the piece and how the materials connect invite deeper thought.

Finishing gallery one is Victor Vasarely’s “Ondho,” one of those oils on canvas that trick the viewer’s perception. A series of horizontal lines are interrupted by curved and offset sections, and these aberrations essentially give the lines a 3-D feel. The piece receives different interpretations when seen up close and far away. The 3-D effect seems to intensify as one steps away from the 7-foot canvas.

Gallery two may be the exhibition’s strongest. On display are publications, letters and photographs from several art collectives; professional communities, even along a periphery that discounts mainstream tradition, seem to be a necessity to support the freedom of many artists. Screenprints of Aktual Art, a Czech publication from the 1960s, are featured, as well as pieces from El Techo De La Ballena (“The Roof of the Whale”) from Venezuela and OHO from Slovenia. If viewers engage with the material and read the many passages of these groups, a greater appreciation for the respective region’s art output is achieved. There are numerous photographs, drawings and prints hanging on the walls and in display cases, so much so that it takes a long time to work through gallery two’s pieces.

In the El Techo De La Ballena pieces, the namesake whale appears many times (there’s more to be seen in MoMA’s education and research building, where a separate installation on this group is housed). Another collective featured is the Gorgona Artists Group, from Zagreb, Croatia, and their publications are on view with screenprinted covers. Take a look for the one overseen by playwright Harold Pinter.

Much of the selections can be considered anti-art, and that’s one of Transmissions’ strongest suits, its ability to let these artists redefine the very definitions of the art world. Look at how Milan Knížák bends and contorts records in his “Destroyed Music” series. His other pieces offer directions and testimonials of his performances. One from 1965 reads: “I Scattered on a Prague Street a Great Amount of Papers.”

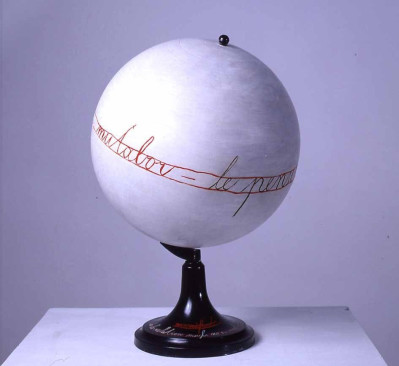

Mangelos’ “Manifest de la relation” and “Manifest diguraski” offer painted globes side by side. Again, there can be some parallels found in this interesting gallery. The intended use of so many objects are discarded and realigned for artistic presentation. The globes by Mangelos (Dimitrije Bašicevic) are meant to offer a different perspective on these simple household objects. By painting over the countries, continents and oceans, the artist must choose to fill in the blanks or leave them purposefully empty.

There’s a sly humor in Milenko Matanovic’s “Summer Projects, The Snake” from OHO in Slovenia. The photographs in this series of projects show a dashed line across a field and river, as if passersby or boaters should follow the direction of the artist.

Lamelas, whose performance piece opens the exhibition, is also featured in gallery three. His “Office of Information About the Vietnam War at Three Levels: The Visual Image, Text and Audio” displays an office setting behind Plexiglass. The set, including a chair, telex and tape recorder, among other items, is a picture-perfect representation of the late 1960s. Visitors are welcomed to listen to Vietnam-era news through a receiver (at times, MoMA has someone inside the office reading the news).

Behind the office art is Oscar Bony’s “60 Square Meters and its Information,” which invites people to walk on a series of chainlink fences while viewing a video of a chainlink fence. The breakdown in perception, of standing on an object and viewing it broadcast on film, clearly defines another of Transmissions‘ central themes: communication. As these artists and collectives operated and protested, they explored the very means of how they communicated to the world. This is most obvious in “Simultaneidad en Simultaneidad” by Argentinian artist Marta Minujín. MoMA displays documents and slides from her performance project that connected people around the world in an artistic presentation of simultaneous action and display.

Lea Lublin’s “Dedans le musée / Pénétration d’images” (“Inside the Museum / Penetration of Images”) broadcasts famous modern-art pieces on vinyl curtains that wouldn’t be out of place in a warehouse. The images are showcased in an almost forgotten-about manner, dropping their significance and highlighting their commonality with ordinary objects. One section of the curtain is missing, allowing passersby to see the next gallery through the projected art pieces.

Lublin’s “Interrogations sur l’art, Discours sur l’art” (“Interrogations into Art / Discourse on Art”) is another of Transmissions‘ highlights. The large fabric features painted-on sentences, all of them redefining the definition of art. In fact, the title for this piece is a nice alternative title for the entire exploration of late 20th century art in Latin America and eastern Europe. These artists, working separately but picking up on central themes, are proudly unconventional, causing viewers to engage beyond simple appreciation. They interrogate; they converse.

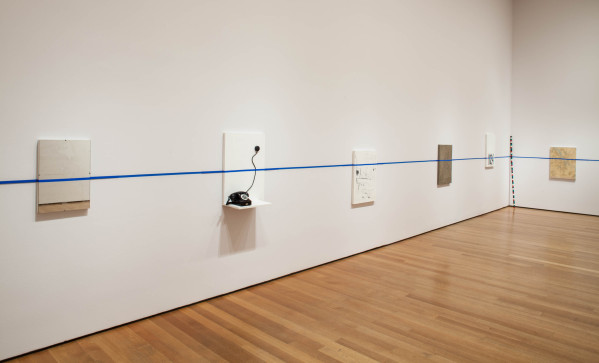

In gallery five, Edward Krasiński disrupts routine borders by lining the room and his art pieces in blue tape. It stretches around the wall, jumping over pieces and tying them together, again asking the audience to consider the connection among the pieces and the installation itself.

Performance artist extraordinaire Marina Abramović, who received a high-profile retrospective a few years ago at MoMA, is represented by one photograph, called “Rhythm 5” from her “Performance Edition 1973-1994.” Abramović can be seen lying down in the middle of a star on fire. Nearby are works by VALIE EXPORT from Austria, Tomislav Gotovac from Croatia and Geta Brătescu from Romania. Several of their pieces play on themes of gender, expression, identity and self-imagery (this last one in terms of Brătescu’s startling self-portrait, “Towards White”).

Sanja Iveković’s series of photos that accompany advertisements is a fascinating look at the artist’s meditation on gender and representation in the media. Her photographs entitled “Triangle” also show a performance piece that played out in apartment buildings and on the streets.

Braco Dimitrijević’s “Casual Passer-by I Met at 4:30 p.m., Berlin” takes a member of the public and offers his portrait in monumental size, giving museum-goers the idea that anyone, including everyday citizens, should have the chance to be exhibited in an artistic gallery. Again, that central theme of redefinition. A series of video installations from VALIE EXPORT and others help drive this point home.

The third central theme, after redefining art and communication, is protest. This is on wonderfully epic display in gallery eight with a series of posters from these two regions. Not all of the posters highlight protests and movements; some are simply theatrical posters. However, they all have a unique style that seems to pull heavily from the fervent energy of the time period. From Roman Cieślewicz’s “Kafka Proces” (“Kafka’s Trial”) to Wiktor Górka and Raoul Walsh’s “Dwaj z Teksasu” (“Two From Texas”), the posters are colorful and abstract, some of them coming close to the Day-Glo posters so popular in the 1960s music scene.

Bony is represented again with a large photograph depicting the members of a family he put on display at an art exhibition. “La Familia Obrera” (“The Working Class Family”) follows Dimitrijević’s lead by throwing emphasis on everyday people and everyday actions.

Perhaps the most famous piece represented in Transmissions is “The Presidential Family” by Colombian artist Fernando Botero. His iconic, oversized images of people posing for the artist are every bit as recognizable as Margaret Keane’s big eyes or Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks (not that these three have any real connection). Botero’s massive canvas can be seen as paradoxical, a portait and simultaneous commentary. The figures are plump and match the shape of the mountains in the background.

León Ferrari’s “Quisiera hacer una estatua” (“I would like to make a statue”) is a blank canvas except for the scrolled calligraphy of continuous words at the top. The piece emphasizes the meta-art of recognition and deconstruction, similar to René Magritte. Beatriz Gonzalez, from Colombia, has a colorful crib in the show. The bed portion of “Lullaby” is painted with a family scene.

Marisol (Marisol Escobar) has one of the largest pieces on display with a painted-wood creation called “The Family.” The members of this group are displayed with faces painted on large blocks of protruding wood. They almost become one with the doors in the background. Marisol is also represented with “Love,” featuring a full Coca-Cola bottle vertically positioned in the mouth of a statue. Brazilian Carlos Zilio’s “1974” asks for a momentary pause; it’s another perspective-confusing piece where arrows are situated at different locations, showing distance and intimacy.

Finishing the exhibition are Běla Kolářová’s “Radiogram of Circle,” featuring images that seem pulled from a Tim Burton movie, and “Five by Four,” a piece that arrays a series of metal paper fasteners in rows. The fasteners are almost like little soldiers, bending at the same angle and aligned in formation. Liliana Porter’s “White” looks almost like a house-painting exercise gone awry. Photographs of white paint partially obscure a human hand, molding the two together, as if the painter wanted to include the hand on the painted wall.

In some ways, MoMA leaves the best for last. Downey’s “Video Trans Americas” places 14 televisions in a room over a vinyl map of the Americas. Each video showcases scenes from places around the two continents. From New York City to Peru, countries, cities and culture are on display, set to evocative soundscapes. For the best viewing, audiences should bend their ears to the speakers on either side of the TVs. For a show that highlights the many intricate developments in art in Latin America and eastern Europe, it seems like an appropriate end to the journey. Plus, it allows viewers to make a full-circle realization. Downey’s “Map of America” helps start the exhibition and his “Video Trans Americas” puts a final exclamation point on these pieces focused on redefinition, communication and protest.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

- Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980 is on display at the Museum of Modern Art through Sunday, Jan. 3. MoMA is located at 11 W. 53rd St. in Manhattan, N.Y. Click here for more information on tickets and hours.