REVIEW: Recent MoMA exhibitions emphasize variety of techniques

NEW YORK — The Museum of Modern Art in midtown Manhattan is having a strong year, thanks in no small part to its beautifully realized Picasso Sculpture show, which closed in February.

The crowds may have flocked to Picasso’s unique creations, but there have been plenty of other gems in recent months. Here’s a sampling of what museum-goers missed.

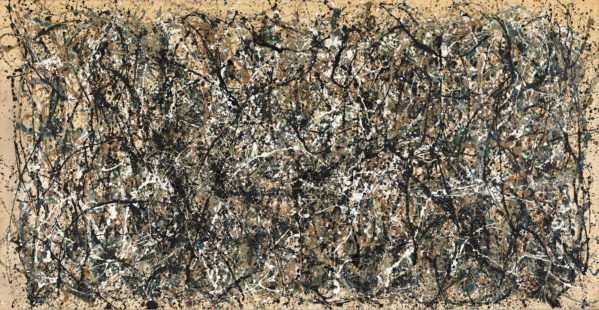

Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey, 1934-1954 was a brief, yet transfixing survey of the always entertaining and uber-popular Jackson Pollock. This artist, feted by generations and subject of so many conversations, continues to impress museum attendees. In fact, his masterpieces — a well-earned term — are major draws in MoMA’s regular collection. That’s why it was so surprising and enjoyable to have a few rooms solely set aside to explore the museum’s unprecedented collection of the master. Known for his dizzying, frenetic displays of splattered paint, Pollock was an abstract painter who reveled in the freedom of new techniques. In the exhibit, there were definitely some characteristic pieces that scream “POLLOCK,” but other ones, such as “The She-Wolf” and “Easter and the Totem,” feature different abstract techniques.

Other pieces displayed Pollock’s wondrous appreciation of three-dimension, from his thickly thrown paint to the nails, tacks, buttons, keys, coins, cigarettes and matches used in “Full Fathom Five” from 1947.

Endless House: Intersections of Art and Architecture explored the many interpretations of house, home and family. Through a series of building models, made with a host of materials, the exhibit allowed visitors the chance to peer down, like a giant, into the windows and doors of these architectural designs. Several of the pieces on display were functional, while others more abstract and intended for an artist’s mind.

Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: The Figure and the Second World War was one of the strongest exhibits of the year at MoMA. Rather than borrowing pieces from galleries around the world, this exhibition was entirely homegrown, featuring selections from MoMA’s own collection. The focus was finely drawn: pieces in the WWII era that touch upon the human figure. From sculptures to paintings to photographs, Soldier, Spectre, Shaman was small in scope but large on impact. Shomei Tomatsu’s “Tomitarō Shimotani, Nagasaki“ was a highlight.

Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015 was a photographer’s dream. The exhibition, featuring many rooms and a wide variety of artists, offered visitors the chance to grab the pulse of contemporary artists in the field of reality-making. The artists took the medium in several directions. Some of the pieces were walk-in installations, such as Lele Saveri’s “The Newsstand” from 2013-14, and others were textual and open for interpretation, like David Horvitz’s Mood Disorder.

Maria Hassabi: PLASTIC was a live installation in which dancers performed throughout MoMA’s stairways, hallways and gallery space. These dancers would appear lifeless, almost as if someone had hit a pause button. Every so slightly and slowly, they would move their arms and legs from one stance to another. They were eternally in slow motion. It was interesting to see them in one pose, go check out another exhibition and then see their progress an hour later.

By John Soltes / Publisher / John@HollywoodSoapbox.com

Click here for more information on MoMA.